It's the quality of life, stupid!

Paul Burall thinks that politicians may have got it all wrong

Most politicians want to make a difference. At heart, they have a conviction that they can improve the lot of the people they represent. Of course, they also want power: this is a necessary pre-requisite for implementing the policies that they believe will make things better, as well as bringing a pleasant sensation of self-importance.

So why is it that politicians are so distrusted? And why is it that fewer and fewer people are interested enough in politics even to bother to turn out for the occasional vote?

Could it be that more and more people are coming to believe that politics is irrelevant, that politicians are seeking the wrong answers to the wrong questions, that political objectives have become disconnected from what people really want?

So what do people want? In a word, happiness. This was even recognised by those who wrote the American Declaration of Independence, who cited the three most crucial inalienable rights as 'Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness' and went on to state that 'It is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its Foundation on such Principles, and organizing its Powers in such Form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness'.

So is bringing happiness to the people the prime aim of politicians today? Of course, any Party that explicitly stated that its core manifesto objective was to bring happiness would be derided.

Nevertheless, most politicians would agree that it is a desirable aim and would claim that, in essence, increased happiness should be the end result of their policies. Unfortunately, the evidence suggests that the politicians have got it wrong.

The political mantra continuing from the latter part of the last century is summed up in Clinton's famous dictum 'It's the economy, stupid!'. Get the economy right - that is, get it growing - and the people will thank you and vote you back into office: that is the accepted route to success on both sides of the Atlantic. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is the all-important measure: increasing GDP will make people wealthier and will therefore make them happier. Right?

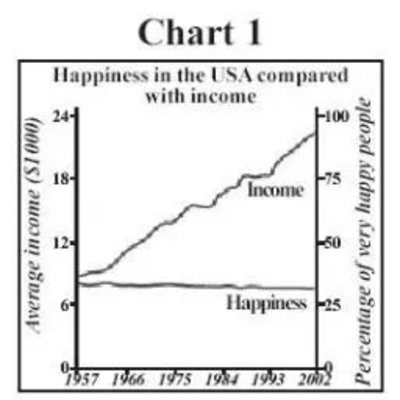

Wrong. Research in both the USA and Britain has shown that there is no correlation between increasing GDP and people's satisfaction with their lives. Chart 1 shows that, while average earnings in the United States have tripled in the last thirty years, the percentage of people who say they are 'very happy' has actually gone down. In the UK, research gives a similar result: while income has increased by three-quarters since 1973, overall life satisfaction has hardly changed. ('Happiness' relates to how people feel about their current condition; 'life satisfaction' is a more general measure.)

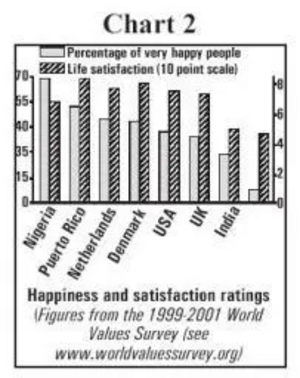

International comparisons make the point even more forcibly: the country with the highest percentage of people claiming to be 'very happy' is Nigeria; and the country topping the life satisfaction ratings is Puerto Rico (see Chart 2).

Of course, Liberal Democrats can sleep comfortably with these conclusions. We have always known that GDP is a poor measure and have argued for alternative quality-of-life measures.

Nevertheless, we have to admit that even within our Party the old arguments about not damaging the economy, the need to help business prosper, the economic advantages of globalisation and so on still bubble up. We still tend to automatically accept the need for continuing economic growth - usually described as 'sustainable', although that is what it usually isn't. Yes, we do qualify this with good intentions about social equity and environmental protection, often with arguments that growth is necessary to produce the wealth that will pay for the equity and protection. Rarely does anyone argue that some kinds of growth are actually bad and should be avoided.

But is making people happy and satisfied with their lives a legitimate political objective? The answer must be yes, for it is what we all want. However, that yes must be qualified, for politicians do not have the power to make people happy: they can merely go some way to creating an environment in which people find it easier to achieve happiness and satisfaction.

Before looking at the policy implications of making happiness a specific political objective, it is necessary to overcome another hurdle. After all, politicians are generally herd animals: most find it difficult to stray far from the accepted nostrums and therefore need convincing that espousing happiness as a political aim will not put them out on the limb of lunacy.

Two trends may convince doubters that the search for happiness is becoming a respectable subject for debate. First, there is a growing body of academic research: it even has its own academic journal, the Journal of Happiness Studies published by Kluwer. Second, some key political think tanks around the world are beginning to take the subject seriously. Even the Number 10 Strategy Unit has published a discussion paper Life Satisfaction: the State of Knowledge and Implications for Government (www.number-10.gov.uk/su/ls/paper.pdf).

Before looking at the kinds of policy changes that might help people be happier, it is worth looking at some of the research into what influences happiness.

The Institute for Policy Research (IPPR) suggests that seven factors significantly affect happiness: income, work, private life, community, health, freedom and philosophy of life. The IPPR dismisses the idea that people in the north of England may be poorer but are generally happier. In a comparative study, it found that levels of depression for men in the Northern and Yorkshire and North-West NHS Regions were three-fifths higher than for the North Thames region and absolute differences for women were even higher. This may be more to do with health than wealth (although the former may, of course, be related to the latter), as the study found that "Self-reported health is strongly related to happiness... People in the North are less likely to report a good state of general health than people in the South."

While poverty does not bring happiness, neither does financial ambition. A study carried out by Tim Kasser at Knox College in Illinois showed that young adults who focus on money, image and fame tend to be more depressed, have less enthusiasm for life and suffer more physical symptoms such as headaches and sore throats. And a survey of more than 16,000 workers in the UK carried out by Andrew Oswald, an economist at Warwick University, found that job status gave more satisfaction than salary.

The acquisition of goods does not bring happiness either. The Roper polling organisation has twice asked Americans to list the material goods they thought important to 'the good life' and both times found that the more of these goods people already had, the longer their list was. So the good life always remained unattainable.

The assumption that the more goods that people can afford to buy, the happier they will be is also disputed by other research. For instance, a recent NOP poll found that around £60m worth of the keep-fit equipment sold in the UK every year is used only once and 10 per cent is never even taken out of its packaging. Another survey, this time conducted by ICM, came to a similar conclusion with a wide range of goods: it found that British homes contained goods valued at more than £3 billion that had never been used more than once.

In the case of food, there is now a crisis caused by the fatal combination of over-consumption and too-little exercise: for the first time, life expectancy is actually decreasing. But this is not a disease of rich people: researchers from Ohio and Boston universities in the United States compared the average wealth of obese people with that of thinner people and found that, while obese people had a net worth of around £70,000, their thinner counterparts were worth £160,000. For every one point increase in the body mass index, annual wealth fell by around £700.

American researcher Tim Kasser is so convinced that consumerism is bad for people that he wants governments to categorise advertising as a form of pollution and either tax it or force advertisers to print warning messages about how materialism can damage health. His point is that since nothing about materialism can help people find happiness, governments should discourage it and instead promote things that can.

There is another factor that needs consideration: the wealth gap. The latest British Social Attitudes survey found a massive 82% of respondents saying that the gap between the incomes of the rich and the poor is too large, the majority believing that it was twice as big as it should be and that it was the government's responsibility to reduce income inequality. Interestingly, most people did not think that the solution was a large increase in salaries for low earners but, instead, wanted a dramatic lowering of the salaries of the high earners. The message seems to be that people are seeking a fairer distribution of current wealth, not an increase in that wealth.

The evidence seems clear: the obsession of politicians with economic growth is not in tune with the key concerns of ordinary people.

What else might influence happiness and life satisfaction?

The Number 10 Strategy Unit's report suggests that cultural values might help to explain the high reported levels of life satisfaction in South American countries, despite low GDP per capita. It is certainly true that different nations seek satisfaction in different ways. In the United States, for example, satisfaction comes from personal success, self-expression, pride, a high sense of self-esteem and a distinct sense of self. In Japan, on the other hand, it comes from fulfilling the expectations of family, meeting social responsibilities, self-discipline, co-operation and friendliness.

Job satisfaction comes through as an important factor in other studies. But the conclusions may not please the present Government. Richard Layard, co-director of the Centre for Economic Performance at the London School of Economics, believes that the pursuit of social status is 'truly fruitless' at the level of society and that devices such as performance-related pay and league tables published to motivate people through the quest for rank are self-defeating. "They condemn as many to fail as to succeed - not a good formula for raising human happiness," says Mr Layard.

Work is clearly important. But it is certainly not a panacea for happiness: half of all British workers apparently believe that their job damages their health. This may well be linked to the fact that, in deference to the GDP-freaks, the UK is the only country in the EU where workers are allowed to opt out of the Working Hours Directive, resulting in almost a quarter of all British men now working longer than the 48 hour maximum allowed elsewhere.

More evidence that our long hours and highly competitive work culture is a cause of unhappiness comes from a 2003 survey by Datamonitor. It found that two million people - 10 per cent of the working population - have already chosen to swap city life for the quiet or rural living or have abandoned high-flying careers for less-demanding jobs. Another 200,000 are expected to join them in 2004. Experts say that downshifting has become a European trend driven by a recognition that time is a commodity that is as valuable as money and what it can buy: they are choosing time over a new Mercedes. But most down-sizers don't move to the country or change jobs: they stay with their employer but in a less-demanding role or working fewer hours.

Further support for the view that people are willing to forego increased wealth for a more pleasant life comes from a recent building society survey that suggested that nearly half of all people aged less than 50 planned to pay off their mortgage early and opt for a more leisurely existence.

A final factor that appears to influence life satisfaction is the degree of control that people feel they have over their own lives. There are many work studies that show that employees who understand how their job fits into their organisation and who have some control over the way they work are more likely to be happy and productive.

This is also true at the community level. For example, direct democracy is beneficial: studies in Switzerland, where referendums are common, suggest people are happier the more they feel in control of their lives. Again, people seem to trust their Parish Councils more than higher tiers of local government, even putting up almost without complaint with levels of Council Tax increase as high as 40 or 50%, probably because they can see where the money is going (interestingly, there are now Parish Councils with precepts approaching the levels of their much-more-maligned District Councils).

There are some obvious lessons for politicians from all this:

- Give priority to policies that provide people with the tools to better control their own lives (for example, by forcing employers to give more choice over working hours and methods; by devolving political power and by involving people in direct decision-making)

- Stop the league-table society that simply divides people and organisations into winners and losers

- Start helping people understand how they can maintain or improve their quality of life without spending more money (for example, cutting energy costs through home insulation or buying long-lasting, efficient products)

- Be honest and abandon Pavlov-dog policies that may please the tabloids but are not the most effective answers (more hospitals and prisons may provide Ministerial boasts but are less effective than better health prevention and a greater concentration on rehabilitation)

- Act to close the income gap between rich and poor

- Tackle the worst excesses of consumerism, most importantly though education so that people begin to recognise that buying more and more things does not, in itself, bring happiness

- Above all, stop claiming that improving the economy is the over-riding priority and accept it for what it is, just one of the tools that can help improve people's quality of life

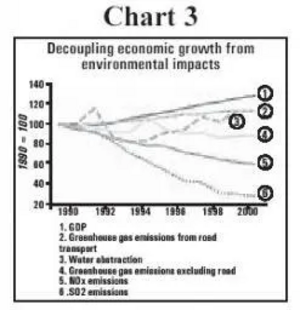

Finally, there is the environment. People living in poor environments are far less likely to be satisfied with their quality of life than those living in a good environment. Fortunately, economic growth has in recent years been largely decoupled from worsening environmental impacts (see Chart 3).

But there is one worrying exception: global warming emissions, while not rising as fast as GDP, are certainly not falling at the rate necessary to prevent climate catastrophe. Late last year, the German government's Advisory Council on Global Change warned that, without drastic action to curb global warming emissions, sea levels could rise by up to 30 feet as a result of melting ice and claimed that even full implementation of the Kyoto protocol would only have a marginal attenuating effect.

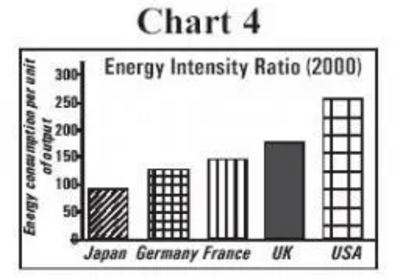

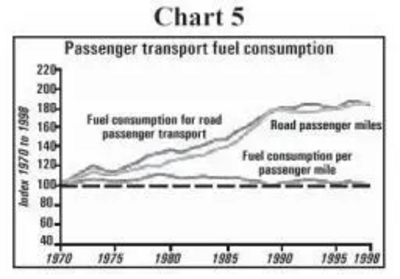

A crucial tool in reducing emissions is, of course, using energy more efficiently. Chart 4 shows that the UK still has a long way to go to match Japan in terms of the amount of energy needed for each unit of GDP. And Chart 5 demonstrates that those who believe that there is nothing to worry about because technology will solve the problem are wrong: despite major improvements in the efficiency of cars, all the energy-saving gains have been thrown away on bigger cars fitted with more and more energy-consuming gadgets.

Perhaps the real message for politicians (at least, for those who believe the overwhelming scientific evidence about the threat of climate change) is to be honest, to tell the public that all is not well and that drastic and sometimes uncomfortable action is essential if future generations are not going to be faced with major threats to their welfare as a direct result of our profligacy.

Too often, politicians trivialise the issues: on the environment, they whinge about packaging and talk about recycling as though it is the answer to the world's environmental problems. So is it little wonder that the public put recycling and litter at the top of the environmental challenges facing us, ranking 'reducing car journeys' as being nine times less important? In fact, when considering the direct environmental impacts of individual behaviour, car use is some six times more damaging than packaging.

In terms of providing an environment in which future generations can be happy and satisfied with their lives, we will know that we have made progress when people start telling politicians that they are prepared to forego a bit of economic growth to protect their children and grand-children from the effects of climate change even if that means leaving their heirs less of a financial legacy.

- Paul Burall is the author of Product Development & the Environment published by Gower. He is LibDem Group Leader on King's Lynn & West Norfolk Borough Council and a member of the East of England Regional Assembly Executive Committee